백남준아트센터

When the body and media become one

It was in March 1963 that Nam June Paik found his way to his first solo show Exposition of Music – Electronic Television in Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal. This exhibition is of paramount importance now that it put media artist Paik’s career into orbit in full swing. It is not only because he brought television as an artistic medium for the first time in art history, but because the concepts explored in his practices of performance were consolidated around the two poles of music and television in this exhibition. Architect Rolf Jährling opened Galerie Parnass at his architecture office in 1949 and he organized more than 160 exhibitions and concerts until 1965, particularly Fluxus actions and happenings of the early 1960s. Here is a sketchy glimpse of Manfred Montwé’s photographs of Exposition of Music – Electronic Television.

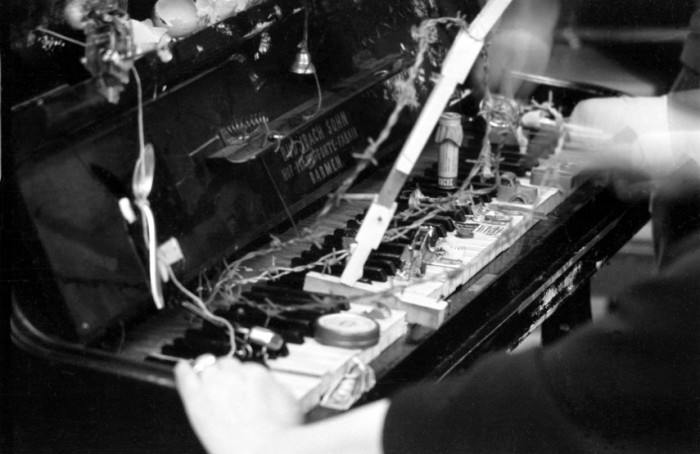

Fig1. Nam June Paik, Klavier Integral, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig2. Nam June Paik, Klavier Integral, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig3. Klavier Integral demonstrated by Gallerist Rolf Jährling, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

In the central hall of the gallery, there were four pianos displayed, a symbol of classical music, under the title of Klavier Integral. The pianos were, however, prepared in the way they could be ‘played’ in a completely different way. The front cases of two pianos were removed, and their keys and strings were covered with everyday objects, all tangled with electric cables. The objects suspended, stuck and nailed on to the pianos were a doll head, a whistle, a horn, a plume, a spoon, a pile of coins, toy sundries, wires, photographs, a padlock, a brassiere, an accordion, an aphrodisiac, a disjoined arm and lever of a record player, and so on. Visitors were invited to play the piano freely. When the keys were pressed, you could hear a strange sound or see objects moving; or you would find that your action of playing the piano turned on a lamp, a siren, a ventilator or a radio in the room. Another prepared piano of Exposition of Music was called ‘Piano for Arthur Køpcke’ modeled on his Shut Books. As Køpcke made a book that could not be read by gluing its pages, Paik slotted a wooden panel inside the piano and closed the lid so that the keys could not be pressed and the strings did not vibrate.

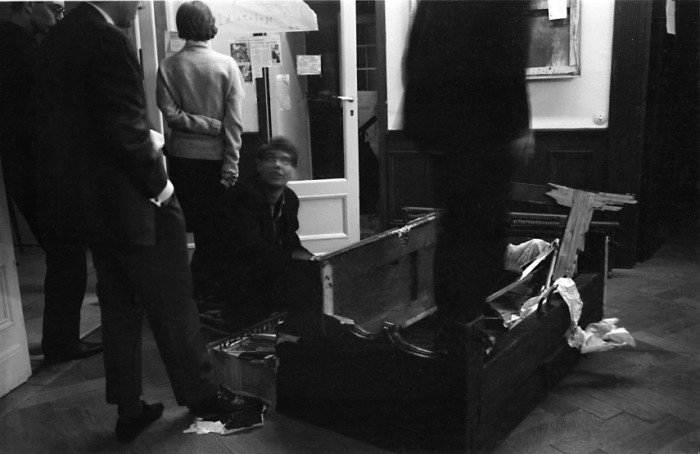

Fig4. View from entrance into the hall with the Ibach piano destroyed by Joseph Beuys Aktion, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig5. View from entrance into the hall with the Ibach piano destroyed by Joseph Beuys Aktion, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

One of Klavier Integral was an Ibach piano, whose lid and hammer were removed and which was laid down to expose keys and strings. Paik’s intention was to allow viewers to tread or run on it, that is, to play it with their feet. In the opening day, Joseph Beuys showed himself with an ax and swung it all the way to strike the piano in shatters. Nobody had known of this happening beforehand, but Paik remembered that the audience burst into loud applause after the improvisational act. It was said that in order to control the situation, Montwé who was in charge of maintaining the exhibition brought a bucket of water to pour it over Beuys. That piano remained there as it was, and visitors watched the sight of a broken piano or stepped over it. It had been actually obtained, with the help of gallery owner Jährling, directly from the Ibachs, one of the two most notable families in Wuppertal – the other, the Engels. Regarding this old piano, Paik recounted: “If the piano survived today, it would fetch a great price because it was the first piano work of Beuys. We did not have a capability to look ahead to the future and returned the broken piano to the Ibachs. They just throw it away.”(1986)

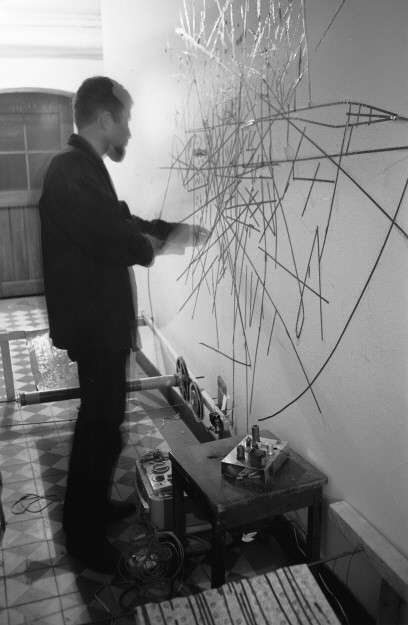

Fig6. Peter Brötzmann demonstrates Random Access, Strips of audiotape, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig7. Random Access, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

After you passed the section of prepared pianos to ‘play music’ down to the basement, you could encounter a section displaying the instruments to ‘play back music.’ A motor-driven cardboard roller was set on two knee-height props. Fragments of magnetic tapes unwound from a spool were attached on a 50cm-wide segment of fabric moving on the roller like a conveyor belt. Tape fragments were also attached like a city map, on the wall between two sets of fabric conveyor belts. Visitors with a metal tape-head separated from a playback equipment went directly to the point they wanted to scrape to listen to the tape. What resembled electronic sounds varied depending on the speed and direction of scraping. Visitors did not listen to the sounds sequentially played back by a machine but they moved themselves to make a sound at a randomly selected spot; therefore, these works were called Random Access.

Fig8. Visitor at Record Schachlik, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig9. Record Schachlik, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig10. Listening to Music through the Mouth, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

There were also record installations across the basement. Upon the radio having a built-in amplifier and speaker, a record player with a turntable was placed. The elongated axis of the turntable was spinning to which ten vinyl records were randomly skewered. Another similar pile of ten records was connected to it by a rubber belt, thus rotating at the same speed. There were two sets of double skewers, so to speak. Visitors holding a magnetic cartridge were invited to access randomly wherever on the records they wanted. The record pile looked like a skewered kebab, so borrowing the word ‘shashlik,’ this work was entitled Schallplatten Schaschlik. A record on the turntable was also used for another work in a rather intimate way. From an antique record player, a cartridge was removed and instead a phallic-shaped object was mounted. Placing a needle on the record, you would hold the phallic device and listen to the record by feeling its vibrations. This is Listening to Music through the Mouth. According to Montwé’s recollections, Paik asked him to take a special photograph, and in the morning when there was no visitor, Paik tried Listening to Music through the Mouth himself to photograph. He transformed the body part that makes sound, into the one that hears sound, with an erotic connotation added.

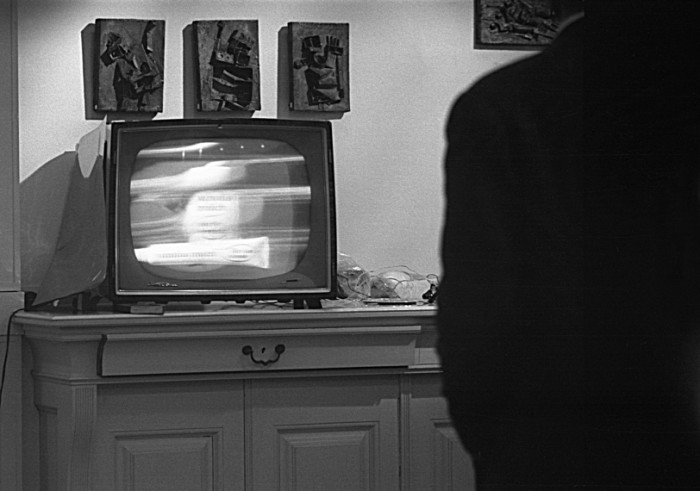

Fig11. Paik working on TV set, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig12. Thomas Schmit in the television room, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig13. Nam June Paik's TV, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

His experimental televisions, i.e., the other pole of the exhibition, did not attract much interest at that time, compared with prepared pianos. In an interview, Paik deplored that people’s attention was diverted to an ox’s head, not appreciating the televisions properly – he was talking about the commotion caused by the head of a freshly slaughtered ox hung above the gallery’s entrance, and just before the exhibition’s opening, forced to pull down by the police for health code violations. Although there were little responses from the audience, the experimental televisions were an outcome of Paik’s rigorous research in cooperation with technicians on television circuitry. In the exhibition, some televisions were those which had been completed in advance while others were barely finished after he repeatedly manipulated circuits in front of television sets at the gallery hours and hours in order to gain the images he wanted. The resulting thirteen televisions distorted broadcast signals into each different abstraction, and no single television showed an identical image.

The experimental televisions may be divided into three categories. Firstly, with televisions whose inner circuitry is manipulated to interfere normal workings of signals, the same TV program broadcast is disturbed by negative images, sinusoidal oscillations, and horizontal and vertical stripes. The second group of televisions is connected to external devices by which the audience is led to participate in making images. Step on a pedal switch or make sound in front of a microphone, and the television screen creates dots of light like sparks; a tape recorder and a radio hooked up to television sets feed sound into image responding to the wavelength of the music and the volume of the radio. Thirdly, there are a couple of televisions out of order, which Paik simply brought to the gallery. In one television laid on its side, a single vertical white line runs through the middle of the screen; the other television set lies face-down showing not the screen but its brand name ‘Rembrandt Automatic.’ Montwé recalled that images on the television monitors ran past rapidly, kept changing constantly, or remained unstable so that it was technically hard to capture them photographically.

Fig14. Nam June Paik's Kuba TV, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig15. Flags by Alison Knowles for Paik's Chronicle of a Beautiful Paintress, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Not only clinging to technical experimentation with televisions Paik took much interest in the political aspects of mass media, affecting people’s minds and infiltrating into social dimensions. For example, there was Kuba TV in the exhibition, a television connected to a tape recorder showing different images depending on the frequency of music input. The title implies the Cuban missile crisis, one week of extreme tension between the Soviet Union and the US, caused by Kennedy’s military command to blockade the route to transport Soviet weapons to Cuba. This was a reaction of the Kennedy administration to the Soviet Union’s support of Cuba’s construction of nuclear facilities. Khrushchev eventually scrapped the Cuban plan seeking reconciliation. Alluding to the political affairs that took place only a few months before his exhibition, Paik created a television whose light waves were in sync with sound waves of a recorder. In another part of the exhibition, there was a framed news article of Bild Zeitung dated 16 April 1961, with a headline “War against Fidel Castro, Invasion has Begun.” On both sides of the frame were four stained flags of Germany, Turkey, the UK and Denmark. This is a work of art by Fluxus artist Alison Knowles. Paik wrote a score Chronicle of a Beautiful Paintress dedicated to Knowles, which instructs her to dye national flags with her menstrual blood each month and to display them in the gallery context. Knowles actualized this score and provided the four national flags for Exposition of Music.

Fig16. Paik in the Library with mirrored foil, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig17. Paik in the Library with mirrored foil, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Unlike other artists mounting an exhibition at Galerie Parnass, Paik’s Exposition of Music made use of the whole building of the gallery as well as the garden outside. In the gallery’s library Paik installed a work entitled To be Naked and Look at Yourself. This was inspired by Ed Kiënder’s work in which circular forms are cut out of mirrored foil and the fragments are rolled up so that its composition forms a still life on which the surrounding space is reflected. With pieces of mirrored foil in gold, silver and red hung from the ceiling to the floor, some of which were crumpled and wrinkled, Paik encouraged viewers to lock themselves in the library and watch their self-images reflected and distorted on the thin paper. This room contained a fan heater positioned upward so that people could feel the warmth between their legs.

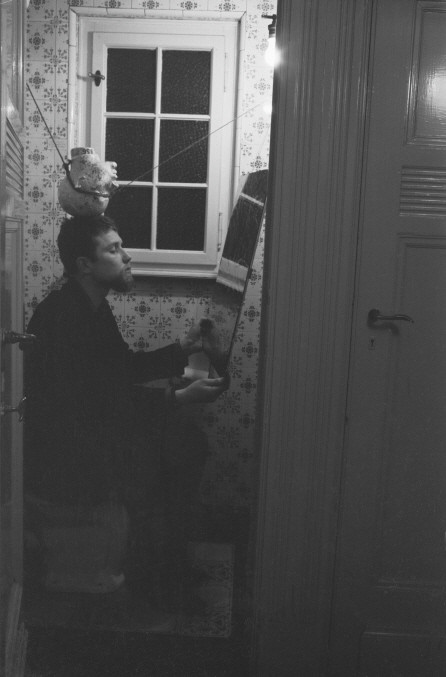

Fig18. Prepared WC, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Foil fragments were also laid on the floor in the Klavier Integral section, on one of which a violin was placed. In the same vein, mirrors placed in front of some experimental televisions can be construed in terms of inserting self-reflexivity in the space. Furthermore, it was in the gallery’s restroom that another mirror appeared, but it was not the one you could normally encounter around a washbasin. It was Paik’s Prepared W.C. in which he suspended a mirror in front of a toilet and a plaster head upside down above it. If you sat on the toilet, the top of your head would touch that of the plaster, and if you looked at the mirror, you could observe four eyes looking back at you. In his childhood Paik loved to spend hours in the toilet, reading an entire issue of Der Spiegel. He even wrote in his 1965 score Symphony No.5 that “3rd JANUARY, 14.68 to 21.00.08: Read for seven hours Baudelaire’s collected works, on the Prepared W.C. sitting like this genius, here Peter BRÖTZMANN (Federal Republic of Germany) or start on the toilet The Brothers Karamazov (Dostoevsky) to read and only come out again, if you have them!!” Next to these sentences are a photograph of Brötzmann sitting on the toilet of Prepared W.C. in Exposition of Music, and a newspaper clipping of the exhibition review from NRZ Wuppertaler Stadtnachrichten dated 15th March 1963.

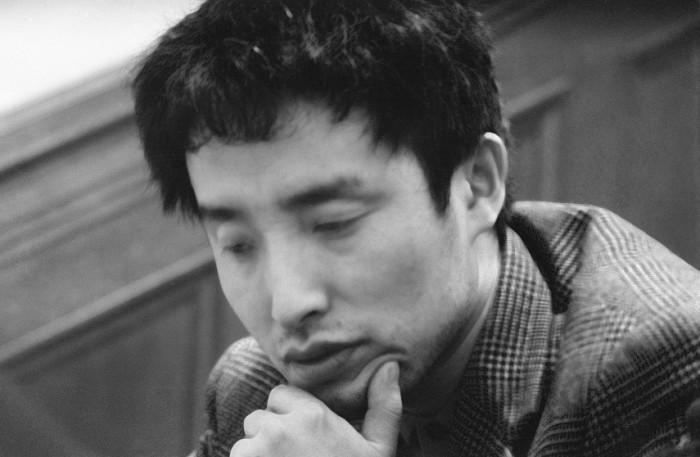

Fig19. Portrait Nam June Paik sitting on the staires, 1963, 30.4x40.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

As manifested in the title Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, Paik raised questions regarding the relationship between visual and audio media, and this exhibition became a watershed in the pioneering trajectory of his move from an experimental composer to a media artist. Fifty years later now, corporeal perception in communication increasingly involves the whole body with advancing media technology. Considering this change, the conflation of bodily senses that Paik realized in the exhibition speaks volumes. He used originally musical objects to evoke multisensory experiences, and non-musical objects to penetrate the space waiting for the participation of visitors. On the staircase, plastic bottles were placed in disarray, and if stepped on, they would be crushed to make some noise. There were telephones by which visitors could make a phone call or simply a dialog. Even a wall relief was intended to be felt only through the face. The mobilization of the space throughout the gallery in which Paik inserted everyday objects was to conceptualize media as an environment. The meanings of his experimental televisions consist not only in the fact that he modified electronic media artistically but that the televisions were part of the environment in which the viewer’s body resides. Employing everything from electronic circuits to a physical building, Paik constructed a productive space in between music and visual art, and out of the space of (in)commensurability a new form of media art began to emerge.

<ggc의 모든 콘텐츠는 저작권법의 보호를 받습니다.>

세부정보

Writer - Seong Eun Kim/ An anthropologist specializing in museology and contemporary art, Kim’s areas of research interest include the material and bodily agency of media art and the sensorial dimensions of art museums in performing knowledge. Having worked in Nam June Paik Art Center from 2011 to 2014, Kim is now in charge of education and public programs in Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

#태그

@참여자

- 글쓴이

- 백남준아트센터

- 자기소개

- 백남준아트센터는 작가가 바랐던 ‘백남준이 오래 사는 집’을 구현하기 위해 백남준의 사상과 예술활동에 대한 창조적이면서도 비판적인 연구를 발전시키는 한편, 이를 실천하는 데 주력하고 있다.