백남준아트센터

Temporality of Photography, Power of Stillness

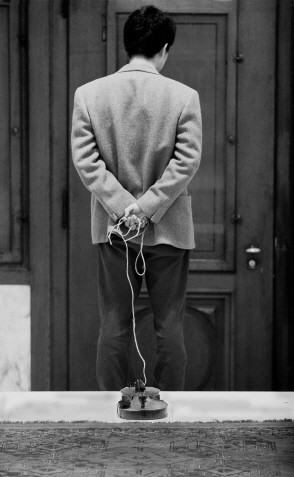

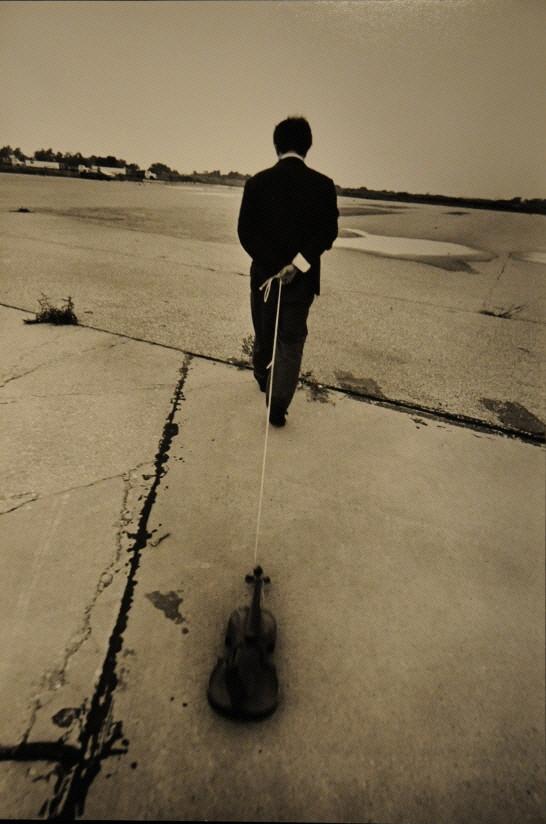

The photographic collection of Nam June Paik Art Center helps you delve into Paik’s active contribution to the Fluxus movement, and his artistic ideas embodied in Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, an exhibition that paved the way for an untrodden field of media art. Further to this, the temporal layers of the collection are deepened by the photographs showing how Paik’s artistic mind born out of this period of time continued to be at play as time went by. Among the photographs of Exposition of Music taken by Manfred Montwé are those capturing Paik walking around the exhibition space dragging a spoon, a toy car’s axle, and a violin tied with a string, as shown in FIG. 1. This is Zen for Walking. Already in 1961, he trailed different objects on the street in Köln, including sandals tied on to an iron chain, a small bell, a head fragment of a sculpture, as well as a violin. He did similar performances many times over the years, and the last one dragging a violin took place as part of the 12th Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York in Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field Park that used to be an airport site. FIG. 2 is its photograph taken by Peter Moore. Zen performed by means of the linearity of a string, sounds made by the dragged objects, Paik’s small but solid appearance from behind, and the accumulated time through repeated and transformed performances over ten years. The resonance of a photograph seems more richly textured than an orchestral concert.

Fig1. Nam June Paik's Zen for walking, 1959, 40.2x30.4cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Montwé © montwéART

Fig2. Nam June Paik's Violin with String, 12th Annual New York Avant-Garde Festival, Floyd Bennett Field, Brooklyn, 1975, 59.5.x40cm, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

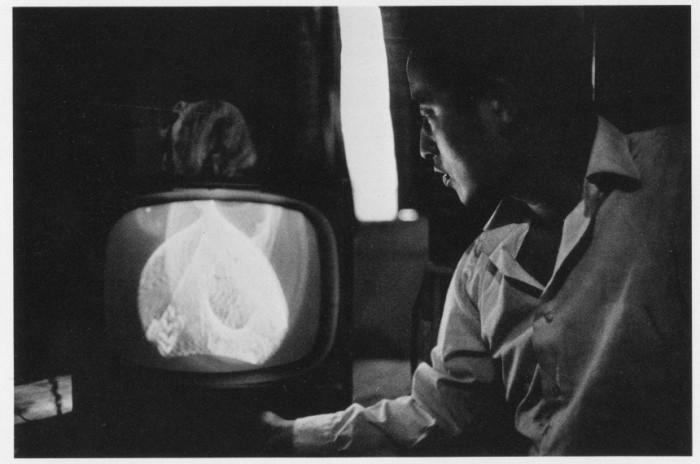

In Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, the title Zen was combined with one of the experimental televisions. A television out of order where only a single line runs through the middle of the screen was called Zen for TV. He once recalled that he had spent a long evening with Joseph Beuys and Günther Uecker, as if doing a Zen exercise, watching the television with a white vertical line cutting across the bluish screen, like a flash of enlightenment. Paik’s ‘Zen’ was also applied to film: Zen for Film shown in New Cinema Festival at the Filmmakers’ Cinematheque in 1965. Organized by the cinematheque’s director Jonas Mekas, this festival presented the works of expanded cinema that merged avant-garde performances and moving images. Paik screened an empty film so that scratches and dust particles on it were projected to the screen. The physical attributes of the film interfering by accident ended up with creating screen images. As captured in FIG. 3, Paik also staged a kind of performance by positioning himself between the projector and the screen, constituting new images by his own silhouettes and movements. Such works as Zen for TV and Zen for Film, which blurred the division of form and content, have less to do with the instrumentality of media to record and represent something out there but more to do with the very materiality of media, hence drawing attention to the media itself.

Fig3. Nam June Paik's Zen for Film(1964) performed as part of New Cinema Festival 1, Filmmakers's Cinematheque, New York, 1964, 40.x59.5cm, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

Fig4. Paik with Magnet TV in his Canal Street studio, New York, 1965, 40.x59.5m, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

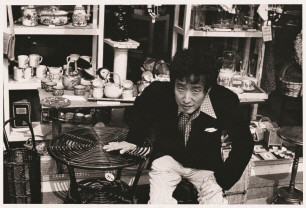

Paik carried on with research into media in technical terms. In order to overcome the limitation of black and white televisions used in Exposition of Music – Electronic Television, he moved on to Japan next year and worked together with technicians there to experiment on color televisions. Magnet TV produced in 1965 was a result of this research. Coils wrapped around a CRT monitor, which is a sort of electromagnet, spread electrons on the screen at a rapid rate. If one touches a magnet to the monitor, the flow of electrons is interrupted such that deflection occurs and distinctive RGB colors emerge consequently. Previously having focused on manipulating the inner circuits of television, Paik turned to what could externally influence TV images, and that is why Magnet TV was produced relatively late in 1965. FIG. 4 is Peter Moore’s photograph in which Paik is handling Magnet TV in his studio on 359 Canal Street, New York.

Fig5. Fluxus Sonata 4 performed at Anthology Film Archives, 1975, 40.x59.5m, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

The experiments on non-linear sound-making in Exposition of Music – Electronic Television reached a phase of more dynamic remixing in the 1970s. FIG. 5 shows a performance Fluxus Sonata No. 4 occurring in Anthology Film Archives (AFA) in 1975. Formerly Mekas’ Cinematheque, AFA opened in 1970, and soon after, it had to move to 80 Wooster Street, New York. During the construction of the new site, Paik’s Fluxus Sonata series was performed here. In Fluxus Sonata No. 4 that deployed several turntables, Paik put an LP on one of them and listened carefully with his arms crossed; and then he moved to another turntable to activate another LP. With the two vinyl records rotating simultaneously, he oscillated between the phonographs, interrupting and spinning them with his hands. Physically intervening in the operation of record players, this performance is much like today’s DJing.

In his 1992 writing Who is Afraid of Jonas Mekas? Paik said that the answer to this question was himself. According to Paik, anybody can have a good idea and anybody can do it for some years, but Mekas’ admirable patience with no promise, with no reward enabled the recordings of his 40-year life, which became a 10-hour single-frame video at last. This is an example of the extent to which Paik did not hesitate to pay a compliment and homage to other artists. Moreover, it was without reservation that he extended his gratitude to those who lent him a helping hand in one way or another. This was often peppered with his humorous eloquence, which is cogent enough to feel the significance Paik attached to being together with others.

Fig6. Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, Charlotte Moorman, Jean-Pierre Wilhelm verabschiedet sich in der Wohnug von Joseph Beuys vom offiziellen Kunstleben mit einem von ihm gestalteten kursen Happening, Düsseldorf, April 1967, 1967, 20.3x25.4cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Leve

As one of the most important events of 1967, Paik picked up Jean-Pierre Wilhelm’s farewell address made to the art world. “Already in his fifties and aware of his impending death, Wilhelm along with Manfred Leve came to Joseph Beuys’ apartment where Charlotte and I stayed. While having a chat, he took a piece of paper out of his pocket and recited a declaration of goodbye to his official art life. The moment was photographed by Dr. Leve. After Wilhelm returned home, Beuys, Charlotte and I giggled at the thought why the old guy had to do such a silly action. But the next year, he simply passed away.”(1986) Fig.6 is Leve’s photograph of the 1967 happening at Beuys’ house in Düsseldorf.

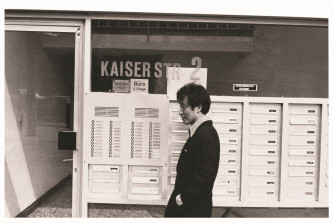

Fig7.Nam June Paik, Hommage à Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, 1978, 20.3x25.4cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Leve

Fig8. Nam June Paik, Hommage à Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, 1978, 20.3x25.4cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Leve

Fig9. Nam June Paik, Hommage à Jean-Pierre Wilhelm, 1978, 20.3x25.4cm, B&W photography

Photo by Manfred Leve

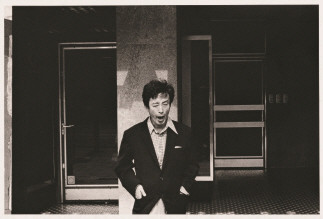

Paik was enormously grateful to Wilhelm since Fluxus could not come into being without him and also he made three turning points in Paik’s artistic career. In 1959 when twenty-five-year-old Paik was unsuccessfully striving to take the opportunity to premiere his first composition Hommage à John Cage, it was Wilhelm that reached out his hands to help the young artist Paik so that he was able to present the work at Wilhelm’s Galerie 22. A lot of artists, emerging and established, came to see his concert because Wilhelm was a star-maker of the German art scene, and hence it was an opportunity for Paik to expand his artistic network. Wilhelm also played a mediating role to realize Neo-Dada in der Musik; he also wrote a foreword to Paik’s Exposition of Music – Electronic Television. Ten years after he passed away in 1968, Paik staged a commemorating performance Hommage à Jean-Pierre Wilhelm on 22 Kaiserstrasse Düsseldorf, where Galerie 22 was located. Walking, running, smiling, yawning, looking at passersby, and pondering. As shown in Fig. 7, 8, 9, Paik asked Leve to take photographs of those seemingly meaningless actions of his. Twenty years after he made a debut as an artist, Paik cherished the memory of a beloved friend and reliable patron of Fluxus, with everyday gestures, with the very Fluxus motions.

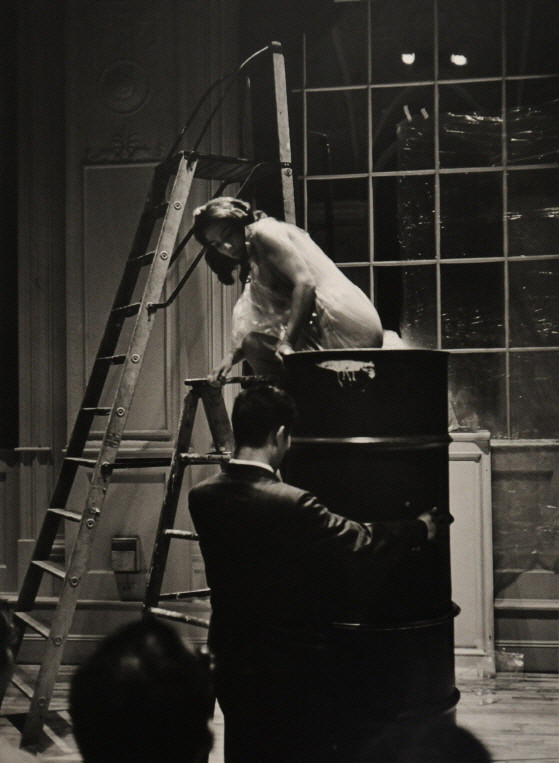

Fig10. Paik and Charlotte Moorman performing Paik's Variations on a Theme by Saint Saens(1964) as part of Paik's Action Music, 3rd Annual New York Avant Garde Festival, 1965, 59.4x43.2cm, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

Fig11. Paik with Charlotte Moorman wearing TV Bra for Living Sculpture, New York, 1969, 49.3x49.5cm, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

“It was spring of 1991. Her last performance was dazzling indeed. Her bow moved swiftly as if a fencing champion wielded a foil. It was as if blue sparks flew up out of the cello. Two things flashed into my mind: an old Chinese saying that the last song of a dying bird is most beautiful, and the genuineness of a last advice of a knight on his deathbed who is afraid of nothing.”(1992) As is well known, after she first met Paik in 1964, Moorman as one of the closest colleagues and collaborators accomplished a lot of projects together with him and willingly responded to his daring performance ideas. FIG. 10 captures a performance of Variations on a Theme by Saint-Saens by Paik and Moorman at the 3rd Annual Avant-Garde Festival of New York in 1965. Wearing a transparent cellophane gown, Moorman begins to play the first few bars of The Swan by Camille Saint-Saëns; abruptly, she puts down her cello and walks across the stage to a large oil drum filled with water. She climbs a stepladder to the rim of the drum where she perches briefly before lowering herself into the water until she gets completely submerged. With the dress and hair dripping wet, she returns to her seat to finish The Swan. In the photograph you can see Paik assisting Moorman in climbing up and down the drum. He once wrote that there were so many works of music that he wanted to listen to in the last day of his life including: John Cage’s Winter Music played by David Tudor, the second movement of Beethoven’s Spring Sonata, or Saint-Saëns’ The Swan played by Moorman.(1992)

For Moorman, Paik not only composed performances but created sculptural works, one of which is TV Bra for Living Sculpture. Playing the cello, Moorman wore two miniature televisions encased in Plexiglass boxes attached to a set of vinyl straps. FIG. 11 shows Moorman putting on TV Bra performed on the cello in the exhibition TV as a Creative Medium at the Howard Wise Gallery, New York in 1969. Videos played on the small monitors of TV Bra varied from live broadcasts and CCTV feeds of the audience around, to prerecorded video footage. The musical notes played by Moorman and the magnets taped up to her wrists distorted the pictures; the cello sounds collected with a microphone transformed images into optical signals to adjust the screens. She did this performance for five hours at the opening, and for the duration of the exhibition, for two hours a day. The text entitled TV Bra for Living Sculpture that Paik wrote about imaginative and humanistic ways of using electronic technology was included in the exhibition’s pamphlet.

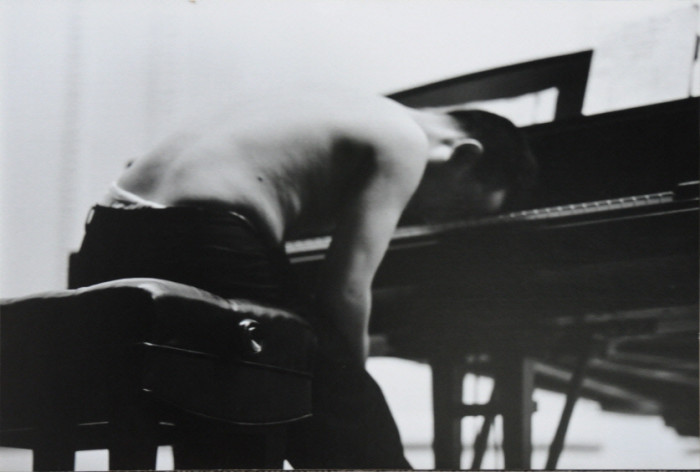

Fig12. Paik improvising during a performance at Town Hall, New York, 1968, 40.4x59.8cm, B&W photography

Photo by Peter Moore © Estate of peter Moore/VAGA

What made Paik-Moorman collaboration widely known to the public most dramatically is perhaps Opera Sextronique in 1967. In this performance, Moorman playing the cello took off clothes one by one in each movement, and when she turned topless in the second movement, the performance was cut short because she was arrested by the police. The ensuing uproar came to have social ramifications upon issues of sexual taboo and freedom of expression in music. Moorman had to go through legal proceedings, and in the wake of her trial Paik and Moorman organized a concert as a fundraiser to pay for Moorman’s legal fees. It was Mixed Media Opera held at Town Hall, New York in June 10, 1968. The repertoire included Arias No. 3 and 4 from Opera Sextronique, which had not made it in the original performance, and other popular Paik-Moorman works such as Variations on a Theme by Robert Breer and Variations on a Theme by Saint-Saëns. Paik’s Simple was also performed here. FIG. 12 is a photograph of this concert in which stripped to the waist, Paik is banging on the keys with his head. In this event, other artists made a guest appearance such as Allen Kaprow, James Tenney, Emmett Williams, and Mekas. The program contained a long text comprised of quotes from a rebuttal to Moorman’s guilt and references for the injustice of the trial.

From the picture, we cannot see Paik’s facial expression clearly. We cannot know what was happening before and after this moment, either. Nevertheless, the very stillness of the moment seems all the more compelling to invite us to get into Paik’s times and into Paik’s people. This is why still images of photography can be more powerful than ever for us, ironically, living in an age where to record and spread one’s every move and every moment quickly and vividly is too effortless. In addition to photographs taken by Leve, Montwé and Moore, the NJPAC collection also contains those taken in the 1990s by Korean photographer Eunjoo Lee, of Paik’s New York studio and a wheelchair he had to rely on suffering from a stroke. Seen through the lens of the photographers contemporary with Paik, he is an artist who, with an open and liberal attitude more than anybody else, never stepped back from the intensity of his artistic life, and who believed “what mysteries the encounter with other people holds for our insubstantial lives.”(1984)

<ggc의 모든 콘텐츠는 저작권법의 보호를 받습니다.>

세부정보

writer - Seong Eun Kim/ An anthropologist specializing in museology and contemporary art, Kim’s areas of research interest include the material and bodily agency of media art and the sensorial dimensions of art museums in performing knowledge. Having worked in Nam June Paik Art Center from 2011 to 2014, Kim is now in charge of education and public programs in Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

@참여자

- 글쓴이

- 백남준아트센터

- 자기소개

- 백남준아트센터는 작가가 바랐던 ‘백남준이 오래 사는 집’을 구현하기 위해 백남준의 사상과 예술활동에 대한 창조적이면서도 비판적인 연구를 발전시키는 한편, 이를 실천하는 데 주력하고 있다.