경기문화재단

Bae Young-whan, Considering Abstract Verb

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern art

This catalogue is published in conjunction with 2017-2018 Korea–Germany Contemporary Art Exchange Exhibition Irony & Idealism. It documents all exhibitions and artworks at 3 venues in Korea and Germany-Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, KF Gallery and Kunsthalle Münster-from September 2017 until September 2018. |

Chang Seung-yeon Art Critic, Art Historian

Artist & Artwork - Bae Young-whan

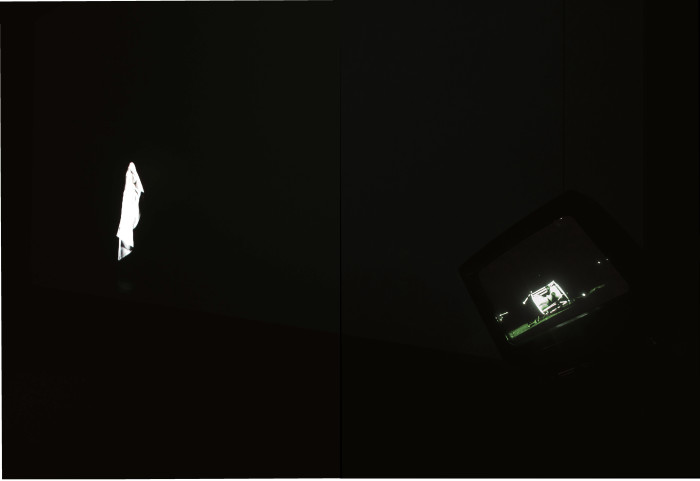

A piece of white cloth slowly flutters within a dark void. The motions of the dancer who grips the cloth are obscured by a dark screen. The whiteness of the flitting cloth contrasts starkly against the black backdrop. All the way through, our eyes search for the serene dancing steps that the cloth makes in darkness, whereas our ears become immersed in the beats of a double-headed drum known as a janggu. The beats reach into the deepest points in our minds. The janggu player is also erased from the screen; only a pair of drumsticks is visible in rapid and florid movement while leading us into a trance— a spiritual state of perfect selflessness. Indeed, in Young-whan Bae’s screen projects entitled Abstract Verb—Dance for Ghost Dance (2012) and Abstract Verb—Knock (2012), the scenes and sounds overwhelm the eyes and ears. In one sense, “overwhelm” does not seem appropriate for the context. What other words could replace it to describe such a pure and sensuous experience? Suddenly, we are struck by the limits of linguistic expression.

These two Abstract Verb serial works incorporate Korean traditional elements in a natural manner. The plaintive cloth flutters in accordance with a dancer’s motion to evoke the Korean folkdance salpuri. The traditional ritual salpuri has been considered to express a dualistic emotional purpose of soothing a deceased person’s sorrow (han) and sublimating it into the excess of mirth. Likewise, the janggu beats on the screen draw viewers into a world filled with extreme joviality and delight. By adopting the peaceful Native American “Ghost Dance” ritual in the title, Bae transforms the dance into a gesture of comfort for the countless people scarified by the violence that has occurred across countless historical, political, and social contexts. However, the subjects that he presents might be familiar to us. The unattended floating shirt that is employed as a tool when performing salpuri appears like the ghosts of unknown people surrounding us. In the dark, the white shirt appears with deep sadness, as if symbolizing the absence and loss of myriad “others.”

After debuting with a solo show in 1997, Bae has shown a range of works that cannot be defined within a single category. He has crossed the borders of numerous mediums and forms, and further suggested an art for the public that extends into the realities of a world beyond artistic spaces. Nevertheless, there is a common factor that contextualizes such diversities throughout his works: his constant gaze at the “here and now” in Korean society. Assisted by this, he has visualized the unseen countless “others” while embracing them into his artistic projects. Through this process, the interpretation of the various messages embedded in his works has engaged the social and political realities of a turbulent era in Korea. In this way, he has been positioned in the “Post-Minjung misul” generational category of Korean art history. Although Bae’s work emerged out of a specific Korean context, it is important to understand that his art has expanded our appreciation and thought beyond a given category by including more universal and fundamental concerns.

Let us consider Bae’s representative works one by one. In an interview, he once stated that, “In this epoch of ours, representative icons made by unknown people seem to be always awaiting artists in the street.” In this way, Bae applies his artistic sensitivity to derive a daily and romantic sensibility from shabby, abandoned, or trivial materials that he has collected. Looking back at his art, his installations have demonstrated a unique formativeness that cannot be explained by social language while describing highly specific icons found in daily reality. For instance, The Way of Man-Guitar that does not cry (2005) is a scrappy guitar made from an abandoned cabinet inlaid with mother-of-pearl. The guitar is transfigured, so it is impossible to play; however, it seems to produce earnest sounds. The Ship of Fools (2007) is an assemblage in the form of a wrecked ship into which insane people who have fallen away from social norms were loaded. However, it also resembles a flower and connotes a floral tribute to these people. Insomnia—Song of Dionysos (2008) is a chandelier comprised of broken glass bottles. It reveals an irony falling between gorgeousness and poverty. Also thought-provoking is an earth represented by a cube rather than a globe in his Impossible Conversation (2012) and Pagus Avium (2016). None of the shapes that have passed through his fingertips pertain to one specific meaning. On the contrary, they have been positioned as an unfamiliar sign, one which includes various meanings for which coexistence would have been considered impossible. Indeed, even in a single moment in which we might try reading a constant narrative into his works, his visual language provides no descriptive clue—it looks like an abstract poem.

The grand-scale installation work Autonumina (2010) displays tiny pieces of ceramics. The impressions of the artist’s fingers in the clay seem, in a sense, simply accidental images. However, the collected pieces visualize mountains or formless brainwaves. It is like the moment of encountering the sublimity of Mother Nature; the moment of visually experiencing the intangible or abstract, such as signals emanating from brains; the moment of vividly perceiving the artist’s activities and senses through the indifferent impressions of hands; or the moment of experiencing speechlessness as if strongly touched by this work. Bae’s art has provided unfamiliar forms through which we cannot help but perceive some of the limits of linguistic expression (as I mentioned before). In a sense, one of the stems stretching out of his various works is stepping onto a different pathway from literary narratives via visual art. It means to search for a representational way, one only available through visual art. So often we have seen that visual art has disregarded things that cannot be explained by language; in contrast, his works have precisely been seeking for or looking toward such things. From this point of view, we can step forward to the sensuous experiences that the series Abstract Verb delivers.

According to Bae, Abstract Verb depends on “‘concepts’ and so provides a different way to approach art that has been occupied by countless ‘nouns.’” An abstract verb does not exist in actual grammar, but in his work it is realized by playing a janggu. Here, the janggu playing itself delivers a vivid and sensuous experience—far from verbiage, it delivers the sense of a fluttering, white cloth in darkness or of being struck into the deepest point in the mind. At the same time, an abstract verb demonstrates a new possibility to reveal that which has been obscured without being verbalized via the instantaneous senses. Here, a new possibility joins together numerous stories of the world beyond art. It is because we often forget the fact, “As nouns come from actions, actions (verbs) change the world.” In a similar context, another of the artist’s pronouncements seems significant, “Is it indeed possible to “speak” realities?”

What Abstract Verb aims to reveal—the “things that are not able to be verbalized”—are, in a sense, the metaphors of the countless “others” who cannot be nominated in the dichotomic terms that social signs create, and eventually, who cannot help but slide off from the sign system. A gesture of rejecting fixture in social language or signs means an escape from the dichotomies that language defines. A motion or choreographic expression cannot be fixed by a single form, and therefore it is said to “formless.” Likewise, an abstract verb resembles an action of escape that breaks dichotomic borders. The artist expunges the dancer and the drummer on the screen while re-approaching their action regardless of its subjects. In so doing, he sparks a creative moment that transcends the borders between forms and formlessness, interior and exterior, real and inner, as well as active and passive, subject and object, and self and otherness. In the end, this representational world seems available only in visual art.

At this point, Abstract Verb—Knock should be reconsidered. From the overwhelming resonance created by the Janggu, we feel, indeed, a trance in which any dichotomic border that may be present is erased. The traditional Korean percussion instrument Janggu has two sides for striking. This means that a single body produces two different sounds. However, the player who creates the sounds has been erased from the screen. That is, when we come to be immersed in the rhythms of janggu, it becomes meaningless to differentiate the player from the audience or one subject from the others. If visual art can do anything in this world, it will certainly be a “different way” of touching a new sensibility within a moment.

<ggc의 모든 콘텐츠는 저작권법의 보호를 받습니다.>

세부정보

IRONY & IDEALISM

Publisher/ Sul Wonki

Chief Editor/ Choi Eunju

First Edition/ July 31. 2018

Published by/ Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art

List of Artists/ Ahn Jisan, Bae Young-whan, Björn Dahlem, Gimhongsok, Hwayeon Nam, Michael van Ofen, Manfred Pernice, Yoon Jongsuk